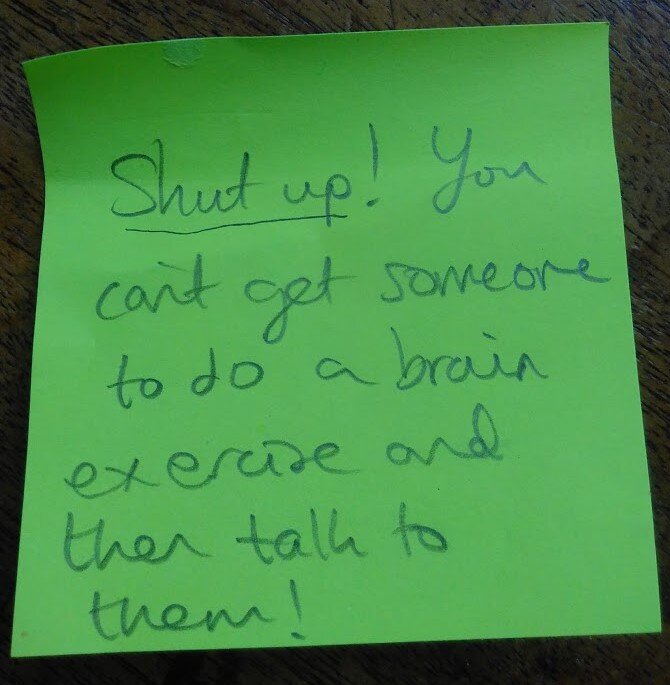

Sometimes I like to give written instructions rather than spoken. For example:

Open your History book.

Write the long date, neatly.

Underline it with a ruler.

Read back through your last piece of work.

Make at least two corrections or improvements.

Pick up the text about the Vikings.

Read paragraph one and highlight any tricky words.

Etc.

Doing this means I have to think carefully about what I want to say, and it encourages me to be precise and concise.

It also means I talk less, which I think is helpful: many pupils comment that teachers talk too much, and I do think that considering what we say, and how many times we say it, is worthwhile.

We all know that some students tune out when we repeat instructions verbally several times. Written instructions mean there’s no need to repeat.

Having given my class instructions that they can easily remember and follow, I am now free to get on with higher impact work such as supporting or challenging individual pupils.

If needed, I can also check in quickly by asking: Nicola, which number are you on? This is effective in focusing others.

Plus this technique is, of course, ‘reading for purpose’ – which I’m a big fan of.

An opportunity to take your teaching to the next level

Three steps to help your class develop their listening skills

Share this 4 minute video with your Early Years colleagues

How to give praise – and how not to – based on the research

Creating the conditions for productive dialogue online, just as we would in the classroom.

The importance of modelling constructive talk.

Simple-yet-effective techniques to get three year olds talking and keep them focused.

Ensure consistency and impact for high-quality pupil dialogue.

Significant improvements in teacher talk and pupil reasoning, before and after a school’s “Talk Project”.

The Director of Oracy Cambridge talks about what the research tells us about effective classroom practice.

A parents’ guide to communicating with children - also relevant to the classroom.